Chappy got out of the house.

It was a freak accident, on a Sunday morning in February. The wind blew the door open, while my husband Ray brought an Instacart order in from the front stoop. The noise scared our cat, our shy, happy, spoiled, fluffy, black-and-white prince, and he jumped through the open door.

Chappy, who hadn’t spent a moment outdoors since he was picked up by a cat rescue group as a baby kitten, and hadn’t shown the slightest inclination to make a break for it in the six years we’d had him, tried to get back inside. He threw himself at the front door, which my husband had quickly closed to keep the other pets from getting out.

With the strong wind, and the closed door, Chappy got scared again. He turned heel, flew down the front path—and disappeared.

I didn’t see any of this happen. I was happily sitting at my computer, messing around on the internet and drinking coffee. My parents were in town from Rhode Island, stealing some sunny Florida weather while New England froze, and I was thinking of the lazy, pleasant day we’d have ahead. Lunch in a nearby beach town, maybe. Perhaps we’d go visit some art galleries.

My husband, frantic, yelled from the doorway that Chappy was gone. We ran outside. We called his name. We crawled through the bushes around our house, in our pajamas. We searched under the cars parked along our street. We couldn’t find our cat anywhere.

As someone who writes about animal welfare for a living, I know that most lost cats don’t go far from home. That goes double for a shy, indoor cat who didn’t really mean to get out in the first place. The experts say this kind of cat is likely to be terrified and hiding just feet away.

All well and good, but Chappy was nowhere to be seen.

We cried, we called his name, my husband went out to an office supply store to make lost cat fliers, while I put Chappy’s picture up on every social media page I could think of—papering Facebook, our neighborhood Nextdoor, and tweeting his photo into the universe, asking others to share and keep their eyes out, and to please help us find the cat I couldn’t quite believe wasn’t home, napping beside our dog Murray, or wrestling with Jack, his best cat friend.

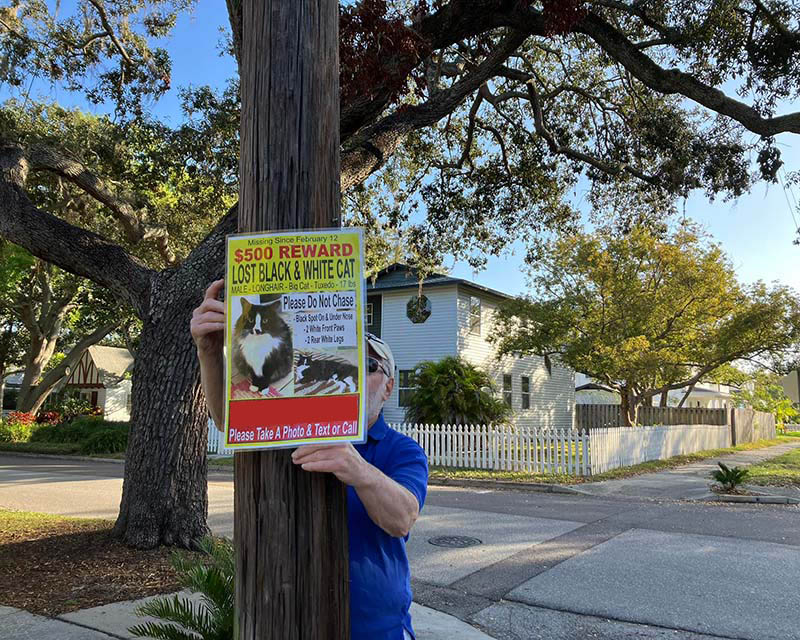

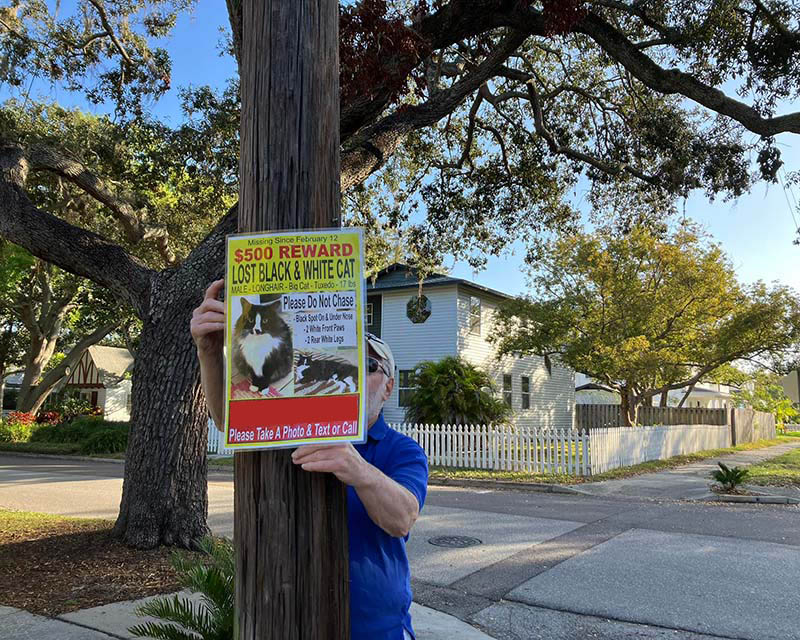

Ray came home, with 100 laminated fliers, and one inadequate stapler. We taped the fliers to stop signs and electrical poles, and to the door of the Little Free Library in our yard. We scoured the neighborhood with flashlights, even though it was daytime, calling Chappy’s name, and crying, and calling him again.

Neighbors and strangers joined in—the very HASS principle of communities stepping up for each other, come to life.

Someone we’d never met before saw us looking and stopped their car to help us search, all of us searching through the trees and the bushes, which had already been checked—but Chappy had to be somewhere. Unless he’d been picked up, or killed, and even then he hadn’t just disappeared.

Word spread quickly and people called, texted, messaged, and said in person that they had ideas for us. Sit in the driveway and talk quietly, so he’ll hear us and come home. Leave the windows open so he could smell the house. Drag a pair of dirty pants around the neighborhood, to create a scent trail. Or don’t, because this might lead a cat in the wrong direction.

Call the cat’s name, to let him know where you are. But don’t call his name, because it will scare him off.

You realize pretty quickly how much conflicting advice there is out there, for finding a missing cat, once your cat is missing. And all you want is for your cat to come home.

Sobbing, we did our best. But there was no sign of Chappy, and it got dark out, and it was still very windy, and we live on a very busy road. Imagining our fluffy prince lost and scared, or worse, we would have given anything, anything, for him to appear.

Some people advised we leave our front door open, so he could just slip back in. But we couldn’t do that, not with two other cats and a dog, and living along that busy road.

Instead we cracked the garage, putting out Chappy’s favorite bed, his favorite scratching post, some food, and a little pile of my husband’s smelliest dirty laundry. Then we did our nightly snack time, for the three pets who were still at home, and we tried, and failed, to get some sleep.

I generally don’t keep my phone in the bedroom, but that night I did in case someone called with a sighting. No one did. We got up over and over to go back outside with our flashlights, and our conflicting advice, and still there was no sign of our missing cat—but I did see an opossum in the garage, munching on cat food.

Over the next days, Chappy still did not come home, and we tried everything we could think of to find him—and I really thought I knew a lot, having written what feels like countless pieces of content about what to do, to reunite lost pets with their owners. We checked with local animal shelters. We left fliers at vets offices, and pet stores, and hair salons. We put up an alert with Petco Love Lost, and installed a Ring video doorbell that went off every few minutes thanks to traffic and wind, and never showed a single image of our cat. A far away friend mailed us some wildlife trail cameras he wasn’t using, so we could try those, too.

We made more copies of the flier and handed them out to people walking their dogs, and put them in mailboxes up and down the blocks near our house. I borrowed cat traps, catching nothing but disgruntled opossums, and crawled under more decks, and roamed more yards. Trying to think like a cat, and specifically my missing cat, I kept returning, fruitlessly, to the same three spots where I thought Chappy might have gone—a fenced yard across the street, a low wood deck next door, and a courtyard down the street where a crew was doing construction.

I worried about our lost cat getting trapped in a garage or a shed or a dumpster. I worried about cars and coyotes, and a hundred other things.

We live in an animal loving area; no one called the police, or said no when I asked to nose around the recesses of their property. People promised to keep their eyes out. Many of them even gave us hugs. They told us stories about cats who’d come home after a month, six months, two years.

A woman I know—we are on the board of an animal shelter together—told me she and her wife were out searching our neighborhood for Chappy every day; they’d made it part of their daily exercise routine. It felt profoundly moving, to have so many people trying to help our cat get home to us.

One woman pulled her car to a stop beside me, while I was out canvassing for my cat again, to say she had one of our fliers on her kitchen island, and that her heart was hurting for us. She told me she had three cats of her own, who she loved very much, and she would be devastated if they were lost.

“I wouldn’t have minded if my ex-husband went missing,” she said to me, before driving off.

We put up more posters. These, brightly colored and eye-catching, were designed by a pet detective—a pet detective!—we’d hired to help guide our search, and who told us that our original fliers were too small, in too few places, and made the mistake of not offering a reward.

The new posters remedied all these problems—though another lost cat expert advised that too many posters could also be a problem, as could be a reward. Anyway, we put them up, my dad using his vacation helping us cover a one square mile radius from our house with dozens and dozens of them.

Some calls came in. We rushed to follow up on every one of them. A small black and white cat two miles away—not 17-pound Chappy, clearly, but why not look. A neighbor texted late at night to say she’d heard a cat making a racket outside her house, and we ran there, too, though we couldn’t find the cat making all that noise. There were a few prank calls, but not as many as you might have expected, given that we’d plastered my phone number on eye-catching posters all over town.

One friend told me she’d had a vision of Chappy in a rust-colored car, while another said she’d had a vision of Chappy under a green set of stairs. I walked the neighborhood, and walked the neighborhood, looking for and failing to find any clues.

A neighbor we’d never met before reached out to say he’d been going through hours and hours of video footage from his home security system, to look for Chappy, and saw a cat who could possibly be our boy. The neighbor texted me the footage. It wasn’t clearly Chappy, but it wasn’t clearly not.

It was the first hopeful sign we’d had in days, and we needed that; we needed it badly. We put up more posters around that block. We knocked on every door. We left more fliers in more mailboxes. The neighbor told us we could lurk around his house any time of day or night, and that his young daughter was looking, too.

Ray and I cried together, and shared our fears together, and expressed gratitude together, that we had each other, that we had a community, that our three other pets were home with us, even if our big fluffy prince was not. The others seemed out of sorts. Chappy’s best friend Jack, especially; he seemed lost without his wrestling buddy.

I’d downloaded a book on how to find a lost cat, which said that a big mistake most pet owners make is giving up too soon, falling into “grief and despair”—the words in the book, which felt very relatable—and abandoning the search as a form of emotional protection. We tried to resist that impulse. We tried to stay positive. We tried to stay hopeful. It was hard to do. We didn’t think we could last a month, or six months, or two years, waiting and hoping for our missing cat. Living in terrible limbo for this amount of time, let alone much longer, felt impossible.

Someone, I wish I could remember who, told me I had to visualize Chappy at home. I had to send that mental image, that faith, into the world.

I am not a spiritual person, I am not religious. But I made myself imagine Chappy napping on our bed, and eating his morning wet food up on the table with the others. I pictured him lying on the rug, next to our dog Murray—Chappy’s favorite being in the whole wide world—and scrapping around with Jack, and rolling over to show his fluffy underside, for the belly rubs that all three of our cats adore. (Elf, our third cat, tolerates the boys; she is an empath for the humans, and made sure that we had lots of cuddles and head butts when the distress grew most acute.)

That night I went for another walk around the neighborhood, with a flashlight and more fliers, calling Chappy’s name, even though some of the experts said not to. I thought I saw a flash of black, crossing a street, a couple of blocks from the house. It probably wasn’t Chappy, but I hoped that maybe it was. I needed to hope. I needed it.

I’d read some advice to make a chum of fish and water, and sprinkle it around making a trail back to the house. (I’d also read not to do this because it can attract other animals, who can scare the cat away.) I decided to give it a try. We also took another pair of Ray’s dirty pants out for a stroll. Why not, at this point. Why not.

At midnight, eight days after Chappy went missing, I got a text from an unknown number. It was someone who said she’d seen our posters. She’d just noticed a tuxedo cat on the far side of the park across the busy street from our house. We’d searched that park, and thought it was unlikely Chappy was there. We thought that our shy boy wouldn’t have crossed the busy road. But he could have, late at night, when the traffic slowed down. We couldn’t completely rule it out. Thc cat could be him.

I asked the person to describe the cat. She said the cat was medium-sized, which Chappy is not. I thanked her, and tried to get to sleep.

She texted back about an hour and a half later.

“I’m sorry to bother you,” she wrote. “But I just saw one that is definitely long haired and could also be yours.” She gave the address where she’d seen the cat. It was right next door. She sent a photo. It was Chappy.

I didn’t wake Ray, who was finally getting some sleep. I went outside, and there was Chappy, in our next door neighbor’s yard. Just where you would expect, if you were following the data and the studies.

I sat quietly and let him come up to me. I pet him, he purred, but when I tried to pick him up, he ran away—dashing under our neighbor’s low deck, exactly where I’d searched for him so many times, crawling along the slats with my flashlight, looking for and failing to find any sign.

I’d had the foresight to bring my phone outside, and called my husband to bring out some cans of food. We put them on the deck, and waited for Chappy to come back out. When he finally appeared from under the deck, he devoured the food. He let me pet him while he ate, and we talked quietly and reassuringly—and then I grabbed my cat, and ran inside.

Chappy was home. He was home! He smelled a little bit like dirt, but otherwise was the same cat who’d left just over a week ago. He was safe, he seemed healthy, he didn’t even look any thinner, and he was home. Thanks to this kind stranger, who’d seen our signs and found our cat in the middle of the night, our family was whole again.

The only thing left was to go around the next day, and take down all the posters. Ray assumed that as his task, and got so many hugs while doing it. He’s not normally touchy-feely with strangers, but the people who cared enough to hug him didn’t feel like strangers anymore.

Then a month after Chappy came home, we got a bad diagnosis for our beloved 15-year-old dog Murray. Murray lived for another month, after that. The only thing that made the whole thing even a little bit bearable, was that we were all home together.

Chappy coming home to us, in the way he did, still seems like a miracle. Sara, the woman who found him, is his angel, and ours, too.

I’ve said to my husband, over and over since Chappy got back, that you could never have planned out the enormous luck required for him to be happily home with us, scarfing his snacks, enjoying his belly rubs, wrestling his brother, missing his dog.

And what Ray says in return, is that by spreading awareness as far and as best we could, and involving our community as widely and as best we could, we set the stage for an angel like Sara to take us the last, incredible step toward our reunion. I think he’s right about that.

I’d known intellectually that neighbors helping neighbors makes us all stronger and safer—that’s the HASS model of community support; we look out for each other, people and pets alike, and we are all better off for it. Now I know it in my bones.

So that would be my advice, too (given with the humility of recognizing that it may be contracted by someone else). If you are desperately missing your lost cat, spread as much awareness as you are able, using the tools and resources at your disposal. Put up signs. Post on Nextdoor. Knock on doors. File a Petco Love Lost report. Stop people as they walk down the street, and ask them to keep an eye out.

Your cat is probably not far from where you live, if they haven’t been moved, and if they are still well (and I hope they are). Draw in your community, if you can, to the extent you can, to help you find your missing pet. I am not a spiritual person. I am not religious. But I’ll bet your neighborhood has its angels, too.

Source: Human Animal Support Services